Here is a snippet of my shell profile where I added -force-with-lease to my alias for force push: #git aliasesĪnd to protect myself in every way I can, I added the following to my.

I run Git exclusively via the command line, often using aliases to streamline (and in this case, protect) my workflow. However, the next best option is to build the preference into your Git usage. Ideally, the default behavior of git push -force would be that of -force-with-lease. The Git documentation recommends this approach to ensure that whatever remote you are pushing to is not the same one that is getting updated automatically by git fetch. In the case that there are background jobs running git fetch, it is possible to work around this by setting up a another remote to push to. In this case, the benefit of -force-with-lease is lost.

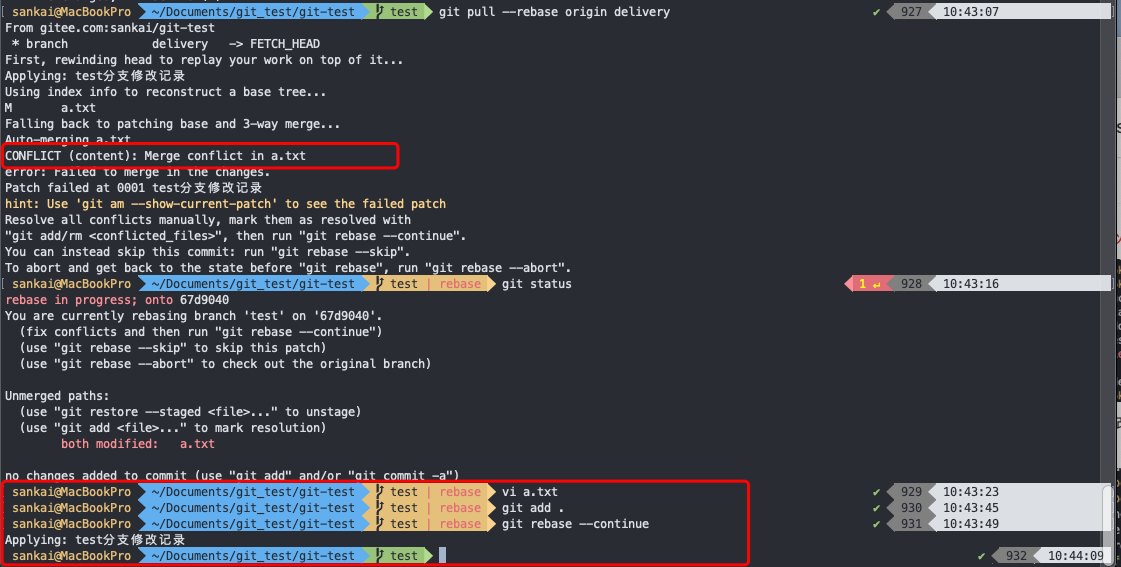

Git rebase force push update#

force-with-lease compares its local knowledge of the remote ref to its actual state, so running git fetch will update the local knowledge without pulling in anything new. It ensures that the history you are amending or rebasing has not changed under your feet. This means that if there are upstream changes unknown to your local repository, the push will be rejected. Instead, -force-with-lease will check that the remote branch is in the state that we expect before pushing. It is hardly a perfect solution, but it is preferable to its blind, wrecking ball cousin. There Is a Safer WayĮnter -force-with-lease. However, the effects are often silent and hard to hunt down, making recovery time-consuming and difficult. Recovering from a forced push gone wrong is not always disastrous, especially when addressed right away. This is where the danger alarms start blaring! If there is any work on remote that you have not pulled, those changes will disappear without you ever hearing about it. When you go to push, the changes will be probably be rejected, requiring a force push. Just rebase off master, push, and call it a day. For example, say that you are finishing work, once again, on a feature branch that is based on an old version of the master. That does not mean you are safe from the perils of force push.Īnother common road to Git suffering takes place when you are rebasing a branch. Maybe you prefer not to amend or squash commits. There starts the long dark journey through Git hell to set things right again. And poof! As you force push, their changes are obliterated. Either way, you’ll soon git push -force and be on your merry way.īut unbeknownst to you, a teammate already pushed while you were tidying up that last commit.

Maybe you squash a few commits, or you go to amend a few more things to your last commit. Imagine that you just finished work on a feature branch, and you are cleaning up your Git history.

When working in a shared repository, this spells danger for even the most careful developer team.

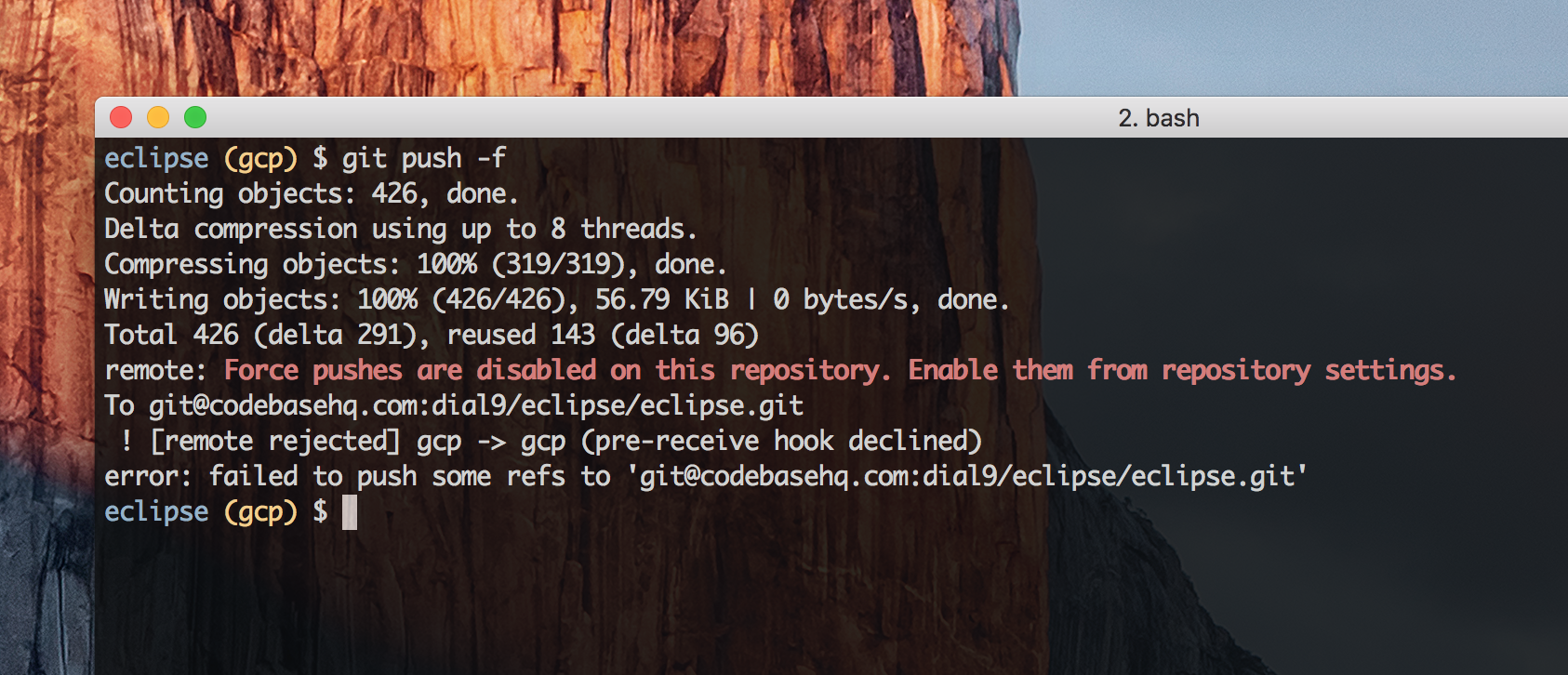

Without question, it will replace the remote with your local changes-and it won’t stop to check if that will override any changes pushed up to remote in the process. It is no secret that git push -force is dangerous.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)